'The Black Hole' Review: Where Disney Went

Then: A half-hearted sci-fi oddity by a flailing studio. Now: I like this movie.

Now Streaming: In the wake of the unexpected success of George Lucas' Star Wars (1977), followed by Steve Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1978), everyone in Hollywood and beyond wanted to go to space, or at least emulate their successes by making their own version of what they did.

Into that superheated dawn of the Geek Age, Robert Wise's stately Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) failed to capture even an iota of its own inspiration, a canceled television show that spawned a raft of rabid followers. (I detailed my own crushing disappointment in an article I wrote for Screen Anarchy some years ago. I stand by everything I wrote then.)

Still, I was young. Since I had absolutely no expectations for another science-fiction picture releasing later that memorable month of December 1979, surely The Black Hole couldn't be any worse? Alas, I thought it was even worse, a pallid attempt by Disney to cash in on a trend that they didn't understand and had no hope of ever comprehending. The presence of Robert Forster, who I'd enjoyed watching as the star of the 1930s private eye TV show Banyon earlier in the 1970s, did little to mollify my overall disappointment.

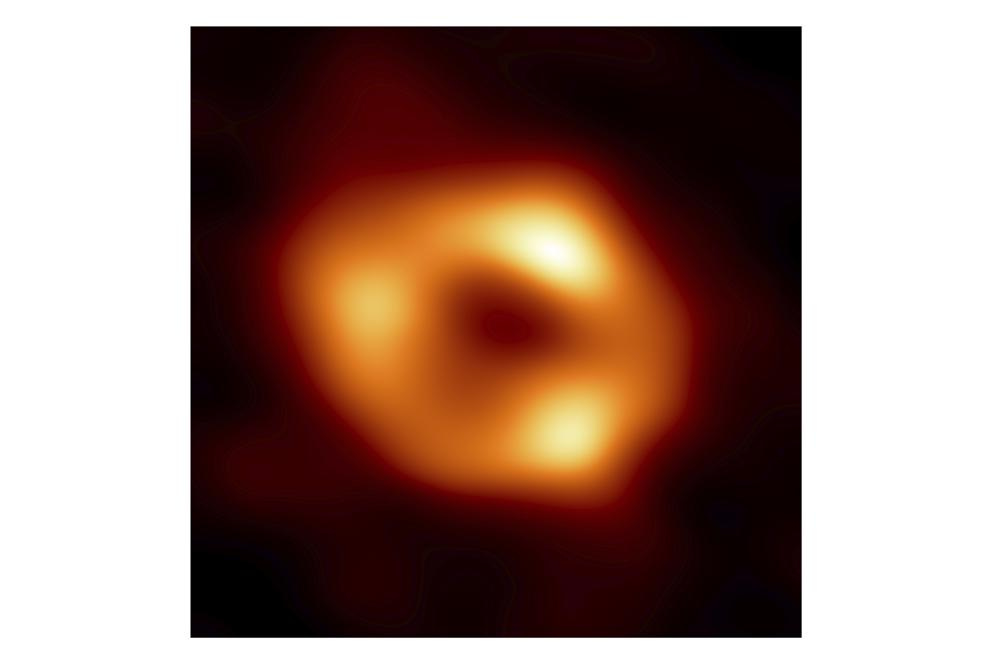

But I remain a foolish optimist. Thus, when news broke earlier this week that the first image of a black hole at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy had been captured, my thoughts turned, of course, to a movie. And what movie could be more appropriate than a crushing disappointment?

The film begins on a grand note with a two-minute musical overture composed by John Barry against a totally black screen, which I didn't recall at all from my single viewing during its initial theatrical release. Voices are then heard as the opening credits roll and a fixed image of a star screen comes into view, which is a pleasantly different way to begin a science-fiction picture and sets the tone for the drama to follow.

Initially conceived as a "space-themed disaster film" by writers Bob Barbash and Richard Landau, inspired by The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974), the script was developed, reworked, and rewritten. After John Hough (Escape to Witch Mountain, 1975) declined an offer to direct, Freaky Friday helmer Gary Nelson came on board after seeing 'miniatures and matte paintings' by the great Peter Ellenshaw.

The spaceship's crew is assembled from younger stars (Robert Forster, Joseph Bottoms, Yvette Mimeaux), supported by old-time veterans (Ernest Borgnine, Anthony Perkins) and a cute robot with big eyes (voiced by an uncredited Roddy McDowall). Their mission is to find undiscovered life, and they detect something worth examining in the vicinity of the first black hole any of them has ever seen.

Looking closer, they escape the pull of the black hole by the skin of their teeth and attach themselves to a ship that was reported lost in space many years before. Once they board, they find Dr. Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell), a bushy-bearded, mad-scientist type, living with a bunch of robots, some more deadly than others. As the crew works to get their ship repaired so they can return to Earth, Dr. Reinhardt informs them of his plan to use the black hole as a slingshot so he can go where no man has gone before.

Forster and Bottoms display a bit of wit in their interactions, but just a bit. Mostly, it's Borgnine complaining, Perkins gazing about at the wonders that Dr. Reinhardt has created, Mimeaux using her E.S.P. to communicate with their robot V.I.N.C.E.N.T., who makes a new robot friend in the drawling, same-model B.O.B. (an uncredited Slim Pickens).

Oddly paced, like many films from that era, The Black Hole keeps its plot simple and its objectives clear. In less than 100 minutes, it tells its story well, and the effects are perfectly fine for what it needs to accomplish. It's interesting to note that this film ended up as the first Disney production to receive a PG rating, for what I'd call a moderate use of curse words and one violent (implied, not explicit) death scene.

Comparisons to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) are apt, since Dr. Reinhardt clearly takes a few cues from Captain Nemo, as well as Forbidden Planet (1956), for which Disney did the effects.

In David Weiner's wonderfully informative article published in The Hollywood Reporter, he notes:

“It was my idea to remove the Disney logo for the picture and use Buena Vista Productions,” [director Gary] Nelson said. “Up to that point, all Disney films were sort of directed for a younger audience, and I didn’t want older people — anybody over 18 — to stay away from the theater if they thought it was just a typical Disney film.”

That was Ron Miller’s sentiment and directive. The producer of the film and president of the studio (who also happened to be the son-in-law of Walt Disney) was angling to broaden the appeal of Disney movies, make them less predictable and usher the studio into a new direction that would include more innovative filmmaking (such as the computer graphics-driven TRON in ’82), the creation of The Disney Channel and the establishment of more mature fare under its Touchstone Pictures banner, starting with Ron Howard’s Splash in 1984.”

Of the ending, which I won't describe here, director Nelson admitted:

“We never had an ending for it. I didn’t like the ending. Nobody liked the ending.”

What concludes the film is strange and weird. Let's just call it metaphysical and leave it to your imagination. As Gary Nelson stated:

“A lot of time and lot of effort to make a pretty good movie. Not a great movie. Not some outstanding movie. But a pretty good movie that will, no matter what, probably stick around for a long time.”

Released amidst a flock of films around Christmastime, The Black Hole did alright at the box office, reportedly making some $35 million, which is not blockbuster money, but not bad against its $20 million budget. It received Academy Award nominations for its cinematography by Frank Phillips, one of his last credits after spending much of the 70s shooting for Disney, and for its visual effects, credited to five talented artists. [Disney+]