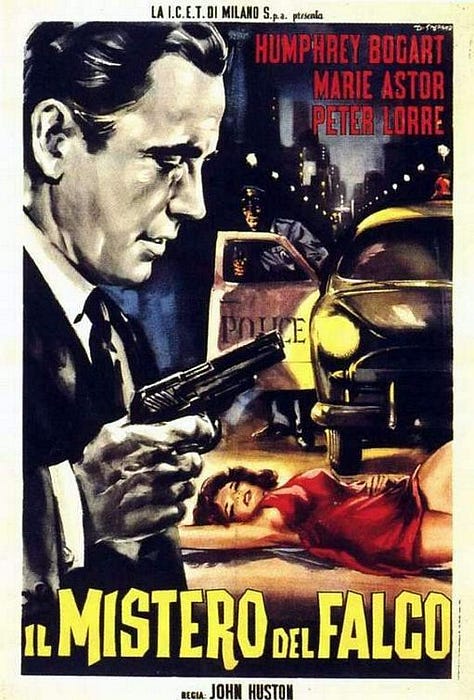

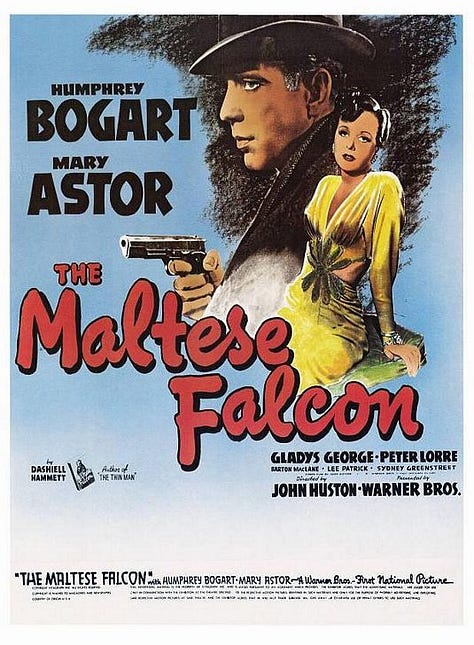

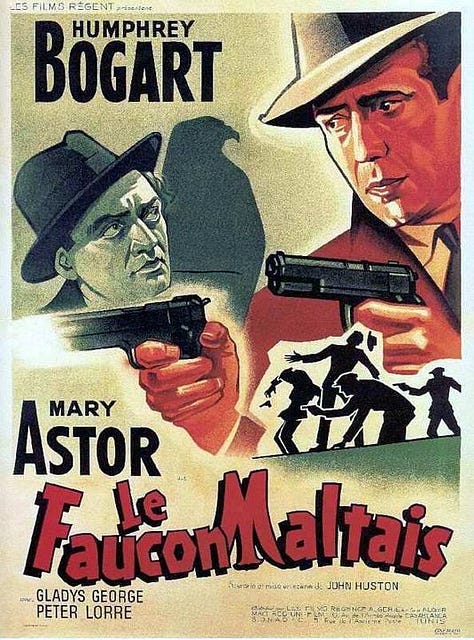

'The Maltese Falcon' Review: Looking Toward Darkness to Come

Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Peter Lorre, Ward Bond and Sydney Greenstreet star in John Huston's directorial debut, now streaming on HBO Max.

Now Streaming: Did you know that The Maltese Falcon is set in the future?

First published as a novel in 1930, the detective story by Dashiell Hammett was swifty adapted for a big-screen version in 1931 (not currently streaming), a pre-code production whose planned re-release was denied by Hayes Production Code censors due to its "lewd" content, including homosexualty and a scene in which the leading lady was strip-searched (per Wikipedia). That led to a comic version, Satan Met a Lady (1936; available to rent or buy via a variety of Video On Demand platforms), that was, reportedly, not well received by anyone, including co-star Bette Davis. (Early in the the novel, Hammett describes Sam Spade's "blonde Satan head," which likely inspired the ill-advised title)

The strip-search scene was dropped entirely by John Huston in his screenplay, though Peter Lorre plays his character, Joel Cairo, with some of the "mincing" that is mentioned repeatedly in the original novel. The strip-search is the penultimate scene in the novel and, by that point, the duplicity of Brigid O'Shaughnessey (Mary Astor) had long been confirmed by her actions. Her true motives are always under suspicion by Sam Spade, in both the novel and in Huston's adaptation.

Indeed, Huston, then 35 years old, included much of the novel's snappy dialogue verbatim, from "When you're slapped, you'll take it and like it" to "I won't play the sap for you!" to Sam's spine-tingling speech to Brigid, just before the police arrive, at the conclusion, though "the stuff that dreams are made of," describing the titular black bird, is a line attributed to Bogart, paraphrased from Shakespeare's The Tempest.

“You’re a good man, sister.”

Huston also dropped something from his script that Sam Spade tells Brigid in private, relating a story that took place "some years ago" involving a man named Fitcraft who disappeared in 1942, to the mystery of his family, and tracked down in 1947 by Spade. It's a very good story, though it's not essential to the primary narrative. As you have noticed, though, that would appear to place the current setting of the novel 'some years after' 1947. Perhaps the early or late 50s? Or even later? (Hammett died in 1961.)

Did Hammett intend to tell one of the first science-fiction stories, just three years after Hugo Gernsback began publishing Amazing Stories in 1926? Was it a proofreading, editing, or publishing mistake? (My personal copy is of the Vintage Books paperback, May 1972 edition, but purchased new by me on April 1, 1982.)

In any event, Hammett's novel is a mystery that quickly absorbed me, which I recall from my first reading back in the early 80s. Initially a five-part serial published in Black Mask magazine, the stories were collected and published as the third of Hammett's five novel. As with his other novels, it features crisp writing, pungent dialogue, distinctive characters and evocative descriptions that make it easy to picture the scene.

Reportedly eager to direct after writing dialogue and full scripts for some 10 years, the son of screen star Walter Huston trimmed the evocative descriptions while keeping most of the pungent dialogue, perhaps realizing that he could not improve upon it, simply by changing the words a bit. I've seen the movie multiple times over the years; my latest viewing on my new, bigger-screened television amplified the visual pleasures that abound.

According to Rudy Behlmer's Behind the Scenes: The Making of … (as quoted by Wikipedia):

"John Huston planned each second of the film to the last detail, tailoring the screenplay with instructions to himself for a shot-for-shot setup, with sketches for every scene, so filming could proceed fluently and professionally."

Furthermore, per David Thompson's Warner Bros.: The Making of An American Movie Studio (as quoted by Wikipedia):

"Huston was adamant the film be methodically planned, thus ensuring the production maintained a tight schedule within their budget. It was shot quickly and completed for less than $400,000."

The film moves like lightning, without ever appearing to hurry. Huston had very good ideas about individual shots and how the camera moved within scenes, which contributes to an atmopshere in which every action appears both spontaneous yet carefully planned. The famed seven-minute, unbroken take is a bravura sequence, even though, while it's playing, it's compelling on its own dramatic merits, not because the shot is unbroken; it doesn't call attention to itself for its technical merits.

From a modern viewpoint, Sam Spade is dapper yet dangerous, a cool cat who gets heated up instantly before dialing it back just as quickly. As suspicious as he is of Brigid's motives, for example, his own motives are under suspicion as well.

Sam is off-handed in off-loading any responsibility to care about his dead partner's wife, Iva (Gladys George), with whom he was evidently involved, and also seems to be stringing along his secretary, Effie Perine (Lee Patrick), who remains loyal him, no matter what he does. He will brook no nonsense from anyone, including heavy-handed Police Lieutenant Dundy (Barton MacLane), prompting his longtime friend and former police colleague Detective Tom Polhaus (personal fave Ward Bond) to intercede and keep Sam from getting himself into more hot water.

The wonderful supporting cast includes stage veteran Sydney Greenstreet, making his screen debut at the age of 61 as the balanced, dogged Kasper Gutman; he and Peter Lorre make a splendid pair, and ended up teaming on nine more movies. Also notable: 38-year-old Elisha Cook Jr. playing Wilmer Cook, or "the kid," as he's referred to by Sam, as well as Walter Huston, making an uncredited, extremely brief cameo.

Filmed at Warner Bros studios in Hollywood during the summer of 1941, The Maltese Falcon was released in U.S. theaters on October 18, 1941. Was it the first film noir? It is for my purposes, which is why I chose to watch it again and make my first entry in this year's cycle of Concrete Fall monthly posts.

As a descriptive term, of course, "film noir" had not yet been coined, but the movie itself certainly serves as a great introduction for the darkness in come in a slew of memorable films that I'll be watching -- or re-watching -- in the coming months. (Also, it's available on a streaming service to which I am currently subscribed.) [HBO Max]